In online instrumental lessons I’m currently finding a focus on exploring new genres and creative activities very helpful in enriching the learning situation for pupils when so many of the normal teaching resources are not readily available. I thought it might be helpful to other teachers to update this project and make it available here.

These are some ideas for creative exploration of a Japanese folk scale by classes/ groups. They may also be of interest to instrumental teachers and individual musicians.

Pentatonic, or 5-note scales, are common in Japanese music. The version of the pentatonic scale, encountered in Western folk tunes contains no semitones but these are extremely important in the Japanese pentatonic scales. In this little exploration, we will work with a scale using:

D Eb G A Bb D (C instruments)

E F A B C E (Bb instruments)

It will be seen that, like our own major scale, this divides up into two identical patterns of intervals. Here, though, each group, is comprised of a semitone and a major 3 .

a) The scale can be played on any melodic instruments available. Practise it

several times, until everyone can play it from memory. Play it at different

dynamics and with crescendi/ diminuendi. (As we will see later, dynamic variation is an important feature of this genre).

b) When everyone is familiar with the scale, it can be used for some ‘call and response’ improvisation. Try this first of all using the A Bb D group for the call and D Eb G group for the response. In this ‘limited note’

improvisation, it is rhythmic assurance and appreciation of phrase length that make for convincing melodies. If pupils are not familiar with this way of working, some practice with predetermined rhythms may be necessary. Actually, in Japanese melodies, the rhythmic conventions differ from those to which we are accustomed.

Later, after some exposure to recorded examples, it would be good to draw pupils attention to these differences in rhythmic organisation. In Japanese melodies, phrases tend to start with long notes and have lots of faster notes towards the end of the phrase. When players are confident with this, more satisfying melodic phrases can be made by adding A to the lower tetrachord and G to the upper tetrachord.

The islands which make up Japan are very mountainous and space for building is scarce. Consequently, the lowlands which skirt the mountains have become an almost continuous ribbon of urban development. Land on which to garden is very precious. Does this, perhaps, account for the preponderance of nature themes in the arts of this most industrialised country?.

c) The scale might be used in group improvisations based on nature themes, e.g.

“Gardens in the Moonlight”, “At the Sea’s Edge”, “Cherry Blossoms”. The latter is the English translation of “Sakura”, probably Japan’s best-known folk song.

In these, pupils should play sparingly, only when they feel their own instrumental sound has something to add at that particular point in the unfolding piece. At other times, giving way to the ideas of others. And always, always listening! It is often a good idea to have a volunteer start with others joining in, as and when they feel it is appropriate. Later, individual melodies can be composed for these titles.

d) If at all possible, listen to recordings of Japanese folk music. Of course, you could do this first but pupils will probably listen with more interest if they have explored the scale and have something in common with the oriental composers. There are many new ideas to take on board.

Two of the most frequently encountered Japanese instruments are the shakuhachi and the koto. Because these instruments have attracted so much interest from pop musicians, every General Midi keyboard has preset sounds for them. If pupils try playing these ‘voices’ after listening to real recordings, though, they are likely to be disappointed. Why do they sound so different? What is missing from the keyboard version? There are, quite likely, three aspects of Japanese performance practice missing or inadequately represented.. These are : pitch bend (microtonal sharpening or, more often, flattening of notes), producing a smeared

effect; vibrato (a wobble in the sound) and lots of swells and falls in the

dynamics. These all feature in Jazz, as well, and are probably the things that have attracted pop musicians to the music.

e) Players of stringed and wind instruments can now try out ways of incorporating these performance practices into their own improvisations and compositions. Here, at last, is a new use for those recorders they thought they had outgrown!) On wind instruments pitch bend is brought about (too often, unintentionally!) By changing the lip formation or making small movements with the mouthpiece of the instrument. Vibrato, as commonly used in flute playing nowadays, is best achieved by creating a pulsation in the air-flow by ha-ha-ha-ing, pushing from the diaphragm. In videos of traditional Japanese shakuhachi playing, though, it seems to be achieved by a skaking of the head and there are several other ways of producing vibrato. These techniques are difficult to do really well but everyone will have a lot of fun trying them out! (We shouldn’t forget that voices are musical instruments and this sort of thing can sometimes free up reluctant singers.)

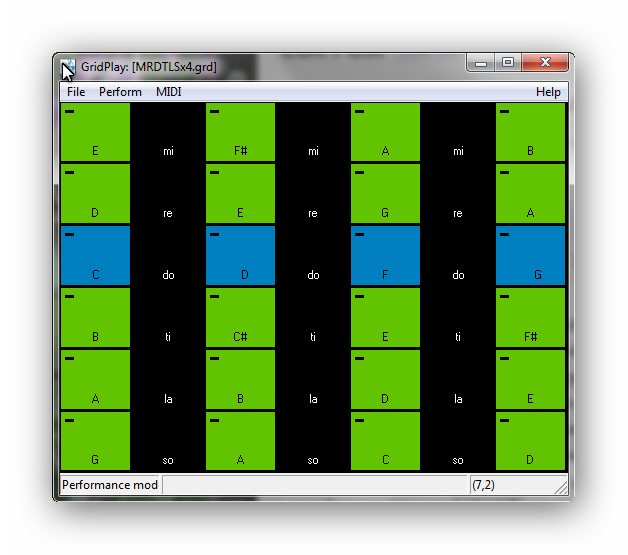

f ) Pitch-bend and changes in the rate of vibrato are not possible on most

classroom keyboards but if your department has more ezpensive keyboards or dedicated synthesizers these will probably have pitch-bend and modulation (vibrato) wheels to add these effects to

the sound. Try playing your ‘shakuhachi’ with these controls and hear how

different it sounds.

g) Individual pupils may now like to try incorporating these effects into their own compositions.

h) Finally, listen to any available recordings of pieces in which contemporary and pop composers borrow ideas from, traditional Japanese music.

Notes on Inclusion

Tuned percussion with removable bars may make the activities more accessible for pupils unable to find and play the pitches on other instruments. If a switch system is available, switches can also be programmed to sound the pitches. A switch system may also afford opportunities to explore pitch-bend.

© Audrey Podmore, 2001,2021

Useful Resources

Many examples of Japanese Folk Music can now be found on YouTube

“The Enchanted Forest – Melodies of Japan” James Galway – Flute. Hiro Fujikake – synthesizers. Japanese folk songs arranged by Galway and original, folk inspired compositions by Hiro Fujikake. Track 6 (Song of the Deep Forest) is an improvisation.

RCA Victor RD87893

(CD/MP3s available from various online sources)

Flute players {and players of many other C instruments) will find free scores for several Japanese folk tunes on the wonderful flutetunes.com.

See also numerous compositions by Toru Takemitsu